The global auto industry is facing a difficult reset as consumer demand has grown more slowly than many automakers and suppliers projected during the post-pandemic surge. Companies invested billions in battery plants, dedicated EV platforms, and aggressive capacity expansion based on forecasts of rapid adoption, only to encounter price sensitivity, uneven charging infrastructure, higher financing costs, and consumer hesitation around range and resale value.

When the industry accelerated into electric vehicles, it didn’t fail because it misread the future. It failed because it mismanaged time.

The recent pullback on EV investments — plant delays, softened targets, hybrid re-prioritization — is often framed as a demand problem. Or a regulatory problem. Or a battery cost problem.

But there’s a more useful lens:

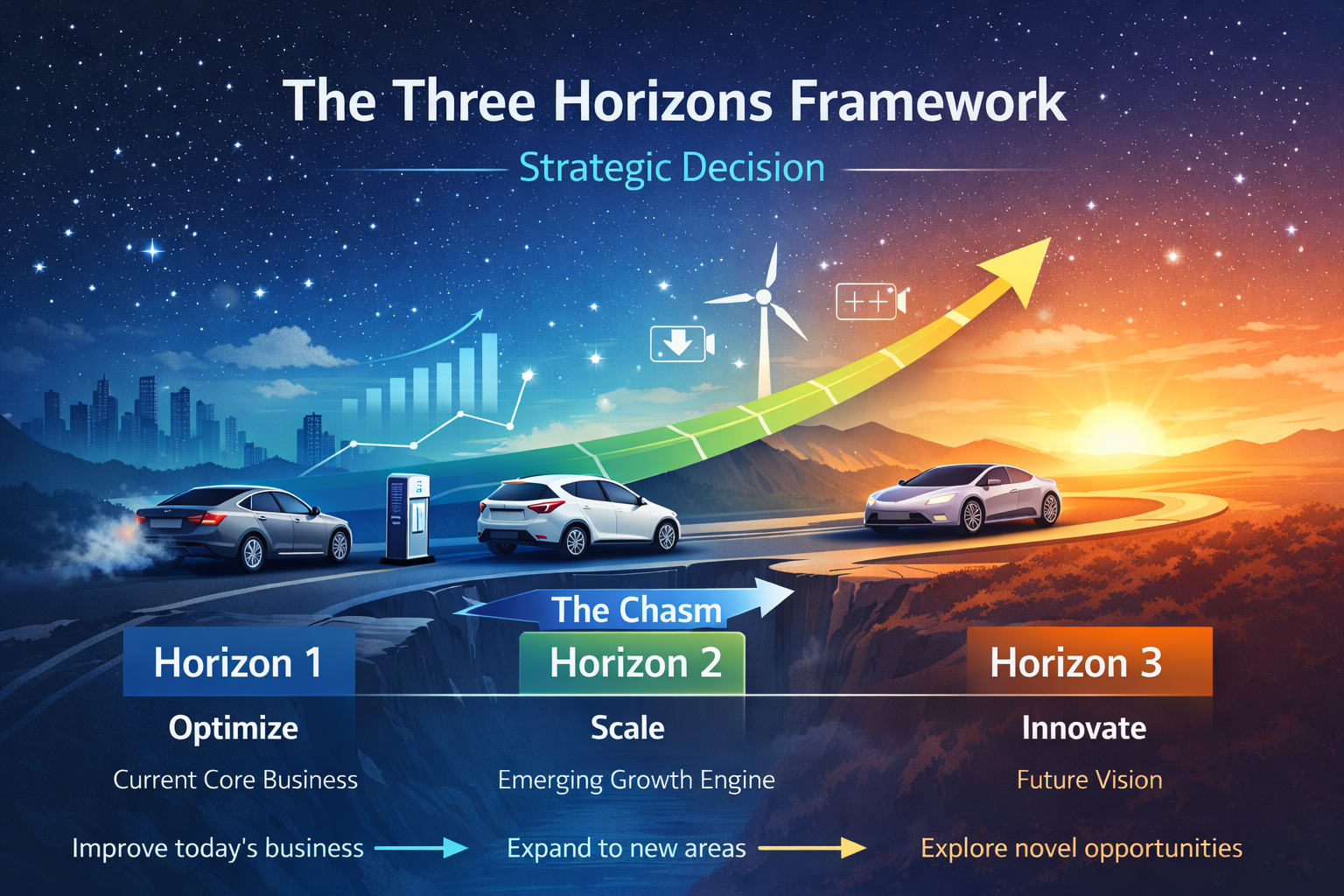

This was a Three Horizons Strategy problem.

Not because automakers ignored the future — but because they collapsed the future into the present.

The Auto Industry Overbuilt for a Future That Did Not Materialize

In the last few weeks, major auto manufacturers have announced massive write-downs for their EV investments.

Stellantis (Fiat, Chrysler, Peugeot) just announced a $26B write off because of ¨slower EV demand and shifting consumer preferences¨. Ford took a $19.5 billion hit and cancelled electric version of the F-150, losing $4.8 billion in the EV division in Q4 2025 alone. General Motors announced a $6 billion charge to unwind excess Ev investments. Porsche was expecting a full shift to electric vehicles, cancelling the next generation 718 and planning to replace it with an electric version.

Industry data shows global EV registrations dropped 3% in January 2026, with particularly steep declines in the U.S. and China, further tightening automakers’ ability to sell and justify prior EV investments.

On February 8th The Telegraph wrote ¨The gamble on electric cars has turned into a catastrophe and it will be many years before the industry recovers¨

The Three Horizons Model (And What It’s Actually For)

The Three Horizons framework, originally by McKinsey but enhanced by Geoffrey Moore in his book Zone to Win, argues that companies must manage three distinct types of initiatives simultaneously: the core business, emerging opportunities, and future bets. The framework reminds leaders that strategy is not just about choosing where to compete today, but about deliberately balancing performance, expansion, and exploration across different time horizons.

Each horizon has different economics, risk tolerance, desired talent profiles, ideal governance structures, success KPIs and investor narratives.

The model exists because what makes you successful today will not build tomorrow — and what builds tomorrow will not look profitable today.

Horizon 1 – Core Business (Performance)

- Focus: Defending and extending today’s core markets and products

- Goal: Predictable revenue, efficiency, and incremental improvement

- Management style: Execution, optimization, operational excellence

For the auto industry this would be Today’s profit engine: Internal combustion (gasoline) vehicles, hybrids, parts, service, & cash flow.

Horizon 2 – Emerging Growth (Expansion)

- Focus: Scaling new businesses that are beginning to show traction

- Goal: Turn promising innovations into meaningful revenue streams

- Management style: Market development, experimentation, and selective investment

For the auto industry this would be near-term growth options: advanced hybrids, regional EVs, software features, and new ownership models.

Horizon 3 – Future Options (Exploration)

- Focus: Disruptive ideas, new categories, and unproven markets

- Goal: Create future growth engines

- Management style: Discovery, learning, and risk-tolerant experimentation

For the auto industry this would be Long-term bets: full EV ecosystems, autonomous, new battery chemistries.

The key insight for the auto industry is that each horizon requires different metrics, funding models, leadership behaviors, and expectations. Treating Horizon 3 like Horizon 1 kills innovation; ignoring Horizon 1 while chasing Horizon 3 kills the company.

Electric Vehicles were a Horizon 2 Bet Treated Like Horizon 1

Electric vehicles not a Horizon 1 business. The Ev market has many characteristics that make it an immature one:

- Uncertain demand curves. Even worse, unclear customer segments or requirements. As Geoffrey Moore explained, early adopters do not behave like the early majority.

- Infrastructure dependencies – from EV charging, standards, to home charging availability. The ecosystem itself is still getting shaped and evolving: batteries, charging software, pricing.

- Cost curves still evolving as battery technology and supply chains evolve. Unstable policy-dependent government incentives.

Consider that EVs accounted for roughly 3.8 % of Ford’s total vehicle sales in 2025 (84,113 EVs from a total of 2,204,124). For Porsche, the percentage was much higher at 22%. Globally, EVs represented 25% of the market in 2025, however that number includes dominant brands like BYD and Tesla that sell only or mostly electric vehicles.

The EV market shows all the typical characteristics of an Horizon 2 investment:

- Businesses are now material in size – 25% of the market, millions of cars

- The segment is growing but not dominant

- Heavy investment is required. The market is not consistently profitable.

- The EV market is strategically critical to the future

The strategic mistake many automakers made was treating EVs as if they would rapidly become Horizon 1 or were already Horizon 1, treating EVs as inevitable, immediate, linear.

- Building (over)capacity assuming near-term dominance

- Underestimating the resilience of ICE and hybrid demand

- Underestimating the reluctance of consumers to change to a new model

- Structuring cost bases for a future that hadn’t fully arrive

- De-prioritizing Internal Combustion Engines, their core business, creating a weakness in their portfolio and a weaker position for today´s business while the future business will take many years to materialize.

Companies Usually Overlook Horizon 2

H2 is the bridge. It scales what works from H3 and transitions what’s profitable in H1. This is probably because a combination of impatience to see the future become a reality, pressure from their board to avoid missing out on the new technology, competitive signaling, and quite honestly, a little (or a lot) of Tesla envy.

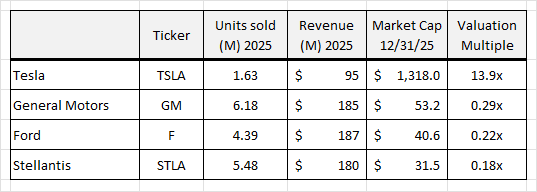

Tesla is valued like a growth tech platform at ~14× revenue multiple at year-end 2025, versus ~0.2–0.3× for the large auto manufacturers in the table below. Even though the incumbents sell 3–4× more vehicles than Tesla, their equity markets price them like cyclical manufacturers, not software-led growth businesses.

Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm model helps explain who buys in each horizon and how long adoption takes — because each horizon is dominated by a different customer psychographic.

When you overlay Crossing the Chasm on the Three Horizons, a clear pattern emerges:

- In Horizon 3, the product is not yet proven commercially. Buyers are technology enthusiasts who value possibility over reliability. Buyers want novelty, performance, access to the future, and being first. And they are OK with tradeoffs like price and long-term viability.

- Between Horizon 2 and Horizon 3 Between Horizon 3 and Horizon 2 sits the Chasm. This is where many industries stall and new products and technologies die. This because innovators buy vision while the mainstream buys risk reduction.

- In Horizon 2, Customers are pragmatic. They want complete solutions, not innovation experiments. They ask: “Who else like me has succeeded with this?” If companies misread Horizon 2 customers as Horizon 3 customers, they overestimate demand.

- In Horizon 1 the ´new´ technology is no longer disruptive — it’s the default. The product category is mature, optimized, and often commoditized. Customers care about stability, standards, efficiency and cost more than breakthrough performance.

The Auto Industry Should have Optimized ICE and treated EVs as Horizon 2

The leading auto manufacturers should have fully optimized ICE (Internal Combustion Engine, or gasoline-powered vehicles)and truck profitability, invested selectively to defend high-margin segments (i.e. minivans), and framed ICE as a cash engine that funded H2 and H3, not a reputational liability. You don’t want to starve ICE prematurely.

An argument can be made that they could have made hybrids the hero. Auto manufacturers have missed an opportunity to dominate the hybrid segment globally. While Toyota sells almost half of the hybrids in the US and had an iconic product with the Prius, there is a positioning opportunity in the mind of customers for one manufacturer to dominate the hybrid market.

Dominating in hybrid would probably provide a foundation to extend leadership to EVs from the perspective of cost efficiency, and would provide valuable demand data to inform EV timing.

Not surprisingly, Toyota executed this far more cleanly than many peers — maintaining optionality without overexposure.

Once companies publicly declared “all EV by 2035,” they removed strategic flexibility. And flexibility is the essence of the Three Horizons model. The model assumes leaders can say: “We believe in the long-term direction, but timing is uncertain.”

Markets often punish that nuance. So horizons collapsed into a single, linear narrative: ICE → EV → Done. Reality, as always, is messier.

What Marketers and Strategists Should Learn

This isn’t just an auto story. It’s a transformation story. We see the same pattern in: AI investments, subscription pivots, platform transitions, and direct-to-consumer expansions.

The failure mode isn’t “missing the future.” We can all agree these are valuable markets that define the future. The failure is treating H3 like H1, ignoring H2, overpromising linear transitions, and funding certainty where uncertainty dominates.

The Three Horizons model isn’t about diversification. It’s about governed coexistence. If you’re using the model correctly, each horizon is allowed to obey its own economics:

- H1 is optimized, not apologized for.

- H2 is nurtured, not skipped.

- H3 is explored, not prematurely industrialized.

The EV reset does not prove that electrification was misguided. It proves that markets mature through customers, not press releases.

The Three Horizons framework teaches us that the future cannot be declared into existence — it must be earned through adoption. In early markets especially, advantage does not go to the company that introduces the most advanced technology first, but to the one that best understands who is actually ready to buy, why they would buy, and what would make them hesitate.

Companies that confuse technological leadership with customer readiness risk building capacity for a demand curve that has not yet formed. The winners will not simply invent the future — they will read the market accurately, pace their investments wisely, and align innovation with the real psychology of adoption.